Improvisation has had a relatively unnoticed history in Western Art until this century whether we look at music or any other seriously considered art form. Because art “objects” have previously been invariably seen as static finished objects the degree of improvisation that must have gone into their production has been largely forgotten or ignored. This even applied in music where the symphony, say, was thought of as fixed at the original intention conceived by the composer, with just a small degree of “interpretation” allowed. This is astonishing when one considers that the sounds were being re-created in front of the audience and quite obviously were not the sounds of the composer. Concert going has thus become most often over the years an activity of recreation rather than a creative event.

The element of “interpretation” that was allowed became relatively insignificant, whereas in reality it was here that inspiration was supposed to take place during performance. Or perhaps inspiration even became an undesirable element altogether! Before this era of written music the level of improvisation in both church and folk music was presumably quite high, and this can still be observed in contemporary more “primitive” cultures. The major difference existing between that period and our own is that we are now aware consciously of improvisation and what we are trying to achieve. Interestingly the use of the word in its present context is fairly new. Improvisation as a word only really became necessary in Western music after the split between composition and performance took place, which co-incided with the rise of a notation system, whereas before it was just naturally part of the process of making music.

If we switch cultures of course we see that improvisation has often been properly ennobled as one of the highest or deepest activities. This is particularly true in Indian and Middle Eastern Classical music. And in tribal and folk music around the world. Its major modern surfacing in western music has been in jazz and with the contemporary developments now reflected in this magazine.

In the visual arts a similar blocking out of consciously emphasised or perceived improvisation has taken place. One has to look at something like Japanese Zen (or Sumie) painting to see a totally improvised visual form. Immersed in up to hours of concentration and meditation on the “object” to be portrayed, the artist achieves a degree of identification with the subject that allows its visual representation to take place in a few seconds with just a few brush strokes. Though not consciously moved, the brush obeys a supra-consciousness rather than the unconsciousness sought by our more contemporary Surrealists. The degree that these Japanese paintings capture the essence of things without in any visual sense portraying their likeness is quite remarkable.

Again we can see contemporary attempts in 20th century painting to catch this improvisational quality, notably some of the Surrealists, Jackson Pollock and the school of Action Painting etc. And since the war and on brief occasions before some filmmakers have been following the same tendency.

The visual arts have probably suffered even more from this previously mentioned lack of awareness of the vital role that improvisation plays in the production of all forms of art. Improvisation has, I would contend, always been the moment of pure creative inspiration and insight in any art form – its importance has just not been properly realised. Thus the classical composer working away within his tonal structures must have had periods of improvisation, usually called inspiration. It has been the failure of the western art tradition that it concentrated on the finished product and ignored the importance of the creative process. There has been an unconscious complicity between artists, critics and the audience in this matter. What seems to be happening now is that in all the arts an awareness of the key value of improvisation is being (re)discovered. And with this is an awareness of process, often even to the extent of ignoring a finished product. Such an ignoring is a stage in an abreaction process. The value of art is as a communication as well as an expression. The work bears witness to the infinite moment of creating.

All this has close relevance to the work I have been doing over the last two years with videotape. Working initially as a filmmaker closely concerned with the interrelationship of image to sound and heavily influenced by music and painting I became frustrated with the limited possibilities by which image and sound could be linked. Seemingly in film one aspect had to dominate, usually in the sense of one process preceding another linearly in time. For example one could start with prerecorded music and cut the images to fit this, or cut a film and then make the music go with the images. But a genuine interplay is very difficult – even shooting images live whilst the music is being played and recorded is frustrating because of the limited possibilities one can put in front of the lens at any one time and the uncertainty with film of knowing exactly what the processed image will look like twenty-four hours later.

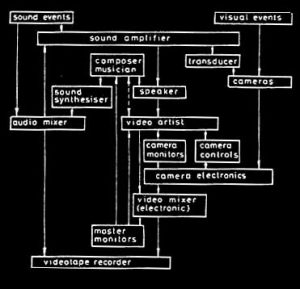

To explore this theme with video we used the set-up in the Royal College of Art colour studio illustrated by the following diagram:

An initial electronic music score is first recorded on magnetic sound tape which forms the starting point of the videotape piece (this was later dispensed with and the soundtrack performed entirely live). Basic images are then formed from this original sound via transducers which can be observed by television cameras. At this point an enormously wide range of manipulations can be made by myself “playing” the remote camera controls to achieve complex colour, apparent texture, size and intensity changes to these images which can also be mixed in several differing ways unique to television. Space does not really allow for the description of how these effects are achieved. They include the normal camera controls such as pan, tilt, zoom, focus and iris. And the great versatility of a’ three tube colour camera which effectively allows the synthesis of any desired colour from three primaries red, green and blue (the primaries for light as opposed to pigment) Black and white variations are effected by an electronic gain control. Pictures (more strictly speaking, signals) are mixed and cut as one sees on normal television. They may also be “keyed” into one another. This is hard to visualise but allows one to colour large blocks of the image in separate colour as in a wood-block print. Or to feed the image from another camera into one of these areas leaving the rest of the picture intact. Also possible are complex visual feedback effects where the camera observes a monitor displaying its own output.

Many other variations are possible and the whole studio set-up can be seen as a unique device for the instant production of moving colour images. The resultant image of all these manipulations can be seen immediately on the television monitor. Simultaneously an additional musical interpretation or improvisation is produced in response to this image by the composer/musician playing a synthesiser and this is fed back into the system. The whole interplay is recorded as a live improvisation between video artist and musician on videotape. As many improvisation recordings as time or desire allow can be made from the original sounds.

To the best of my knowledge this degree of improvisation between music and a non-figurative visual art is unique, and has only become possible because of the capacity of the new electronic medium of video to allow the immediate production and viewing of a very complex constantly changing image. This new form lies at the conjunction point of film, painting and music. It has been called “electronic painting” though “an electronic produced visual and sound improvisation” would be more accurate.

Part of the hostility that has existed in western culture to improvisation has been simply through misunderstanding. And this has not been helped by those artists and musicians who in their desire to reject old forms have over-reacted and created totally spontaneous forms. Such productions, whilst being quite often great fun to the performer(s) usually lack sense to the perceiver. Some degree of structure is necessary. Chaos is perceived in its reflection, order. And spontaneity enhanced by contrast with structure.

At the conjunction point of these opposites lies improvisation at the high point of creative activity. It bears witness to a single point of concentration and awareness in the artist’s being. Prearranged contrived over-intellectualised structures are dead at any real level. And purely spontaneous acts lack the force to communicate their joy to others. Improvisation is the meeting ground of these two acts where art is born. Whether the result of this peak moment is paint marks on canvas, the rearrangement of magnetic particles on a tape or nothing at all except some dying echoes in an empty hall is completely beside the point. All that matters is whether a moment was laid bare. If it was, that is enough in itself. Homage has been made.